Yamazaki Hiroyoshi

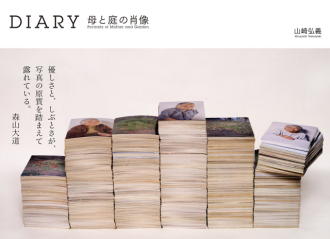

photo book "DIARY Portraits of Mother and Garden " Hiroyoshi Yamazaki

My mother showed no expression today. I entered into the garden and found all of the Chinese

violet cress coming into full bloom. I felt the change of the days. I shot my mother, who has

dementia, and my garden almost every day for three years like a diary.

The period was from September 4th, 2001 to October 26th, 2004, when my mother died.

The photographs totaled more than 3600.

Beginning in 1999, my mother’s memory started to fail and she started to experience

troubled behavior like wandering around and having emotional turmoil. I was an only

child, so I had to care for her. Fortunately, our caretaker cared for her during the day and

my wife and I did it nights and weekends. She sometimes showed a calm expression, but

sometimes had troubled behavior. At last she tended to forget my name, but those expressions

of hers are in the photographs.

I tried to shoot a corner of my garden after shooting my mother. The contrast between

my mother approaching her death and plants showing different looks according to all four

seasons. After I started to care for her, I somehow came to feel curious about the breath of

the plants. I tried to highlight these two states of life through fixed-point observation.

It was the New Year’s holiday of 1998. We had New Year’s food at Ms. Sumiko’s parents’ house.

When we went back home, my mother said “I wish you a Happy New Year,” which in Japan is a greeting

only used up until December 31. It was just a slip of the tongue, but now I think this was an obvious

sign. She was always said to have a bad memory and I had her see a nearby psychiatrist, but it was not

a big problem in everyday life. Even a specialist could not figure out if it was a mild dementia or elderly

depression. I don’t know if she had a feeling that something had slipped out of her head, but she left

notes everywhere at that time. However, she often forgot where she had put her noteboook and bought

a new one.

Next year, when the autumn breeze blew, she started to wander about at night. She said, “I don’t

want to lose my ability to walk,” and got in the habit of taking a walk in the neighborhood around 9:00

p.m.. I didn’t want her to get lost, so I followed her. She took a walk at night two or three times a week.

One day she came back home bleeding from her hand. She seemed to have grabbed the barbed wire in

front of our house. These wanderings were a heavy burden on us, but fortunately it stopped immediately

after she took a pill prescribed by a psychiatrist.

After I came to care for my mother, I couldn’t even go out. However, I always thought I wanted to

shoot my mother’s photo. I couldn’t decide on my shooting procedure, for example, what kind of camera

I would use, and with what composition I would shoot. I bought a medium format camera, a Mamiya

7, but it was not suited for a portraits because it lacked zoom. I decided to use a Fuji GA645Zi, which

I always used for street snaps, and it ended up really working. I could take a bust shot with minimum

shooting distance and easily release the shutter with auto focus.

I started to shoot from September 4th, 2001. I always did it in the morning, because my mother

had a clear memory and she followed my advice in the morning. She often fell into delirium at night and

she was restless or fell asleep. When I woke her up at 6 o’clock in the morning, I got her changed, gave her

breakfast and medicine. The medicine was composed of 6 pills. When the pill got stuck between her

false teeth and her gums, she spat it out. I had to check if she swallowed it completely. Especially, if she

didn’t take her medication for hypertension, her blood pressure would rise rapidly. Special caution was

needed. After I gave her medicine, I took a rest and got around to shooting. I got accustomed to the

procedure, so it took only 10 minutes. My mother didn’t refuse it and she kept quiet and got photographed.

In doing this, I always asked her these questions.

“What is your name?”

“When is your birthday?”

“What was the name of your husband?”

“What happened to your husband ?

“Where did he work?”

I tried to keep these memories in her by asking these questions everyday.

Why did I start to shoot from September 4th? Because it was the day that fate fell on us.

September 4th, 1990, 9:25 a.m. While I was working, my mother called me to say that my

father had a stroke in Ueda city. His condition was bad and we had to go to the hospital at once. The

diagnosis was a critical brain infarction and the doctor said that this week would be the most important

for him. Fortunately, he escaped death but he could not even roll onto his back and was confined to bed.

My very petite mother had been caring for my father, who weighed about 70 kg, wholeheartedly for

about 6 years. My mother developed dementia several years after that, but I decided not to move her

to nursing-care facility. That was truly because I had been watching her caring for my father. When he

failed to move from bed to his wheelchair, she gave me a call for help many times. When he went to a

day care facility once a week, I drove him to and from there. When I came to pick him up at half past

four o’clock, my father and my mother would often wait for me at the window. The scene was still burned intomy memory.

Despite these memories of my father, caring for my mother became really stressful.

We all have our limits of tolerance. The limits vary from person to person. For example, some have

a small capacity, like a test tube, others have a large capacity, like a bucket. Some days there is nothing

in the container, but other days it is almost filled to the brim. When the container spills over, people vent

their frustration. I believe my container is larger than an ordinary person, but my frustration sometimes

spilled from the container during the six years of caring for my mother. That was due to the behavior

unique to dementia. I did understand it was due to the illness, but my frustration slowly, or sometimes

suddenly, collected into the container and spilled from it.

I couldn’t stand my mother changing from what she used to be. I think I tried to confirm my own

horizon and keep my mental balance through the expression of shooting every day.

Furthermore, the moment I released the shutter, I always asked myself how long this was going to

last.

However, I clearly understood I was living an irreplaceable moment.

On October 26th 2004, my mother Iku completed her living and passed away at the age of 86.

Separation, then release from life.

Afterword October 26, 2014 Hiroyoshi Yamazaki

Everything is already contained in my memory. However, these

photographs remind me of the days that I struggled in that dark tunnel

for a little light. When I read the diary again, I found myself reaching the

limit of my patience at that time. I feel a pang of regret because I should

have treated her more tenderly. At the same time, however, I believe I

had a lot of good luck during that time. God could have given us a much

worse scenario.

In editing this photo book, I put my mother’s note written in 1999

at the front. My mother in the photographs has been silent, but with this

note I felt as if she started to speak loudly.

While I was making this book 10 years after shooting these photos,

I had a slight hesitation about publicizing it. However, I desperately

wish that these photographs reach those who are suffering and become

some kind of hints in their lives.

Published in 2015

by Ohsumi Shoten, Publishers

Rm#505, 5th Floor Komazawa Building

5-16-12 Honkatata, Otsu, Shiga 520-0242 Japan

E-mail: info@ohsumishoten.com

Web: http://ohsumishoten.com/

Copyright c 2015 by Hiroyoshi Yamazaki

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior permission of Ohsumi Shoten, Publishers.

Design: Takashi Kitao (HON DESIGN)

Printing: SunM Color Co., Ltd.

English translation: Kazuma Kiyota

English proofreading: Seanacey Pierce

ISBN(japan) 978-4-905328-09-4 C0072

Printed in Japan

Critic ( japanese )

Keijiro hosaka Asahi Shimbun 2015/4/19

Koutaro iizawa Artscape 2015/4/15

Koutaro iizawa Artscape 2015/5/15

| |

DIARY Portraits of Mother and Garden |

|---|

violet cress coming into full bloom. I felt the change of the days. I shot my mother, who has

dementia, and my garden almost every day for three years like a diary.

The period was from September 4th, 2001 to October 26th, 2004, when my mother died.

The photographs totaled more than 3600.

Beginning in 1999, my mother’s memory started to fail and she started to experience

troubled behavior like wandering around and having emotional turmoil. I was an only

child, so I had to care for her. Fortunately, our caretaker cared for her during the day and

my wife and I did it nights and weekends. She sometimes showed a calm expression, but

sometimes had troubled behavior. At last she tended to forget my name, but those expressions

of hers are in the photographs.

I tried to shoot a corner of my garden after shooting my mother. The contrast between

my mother approaching her death and plants showing different looks according to all four

seasons. After I started to care for her, I somehow came to feel curious about the breath of

the plants. I tried to highlight these two states of life through fixed-point observation.

It was the New Year’s holiday of 1998. We had New Year’s food at Ms. Sumiko’s parents’ house.

When we went back home, my mother said “I wish you a Happy New Year,” which in Japan is a greeting

only used up until December 31. It was just a slip of the tongue, but now I think this was an obvious

sign. She was always said to have a bad memory and I had her see a nearby psychiatrist, but it was not

a big problem in everyday life. Even a specialist could not figure out if it was a mild dementia or elderly

depression. I don’t know if she had a feeling that something had slipped out of her head, but she left

notes everywhere at that time. However, she often forgot where she had put her noteboook and bought

a new one.

Next year, when the autumn breeze blew, she started to wander about at night. She said, “I don’t

want to lose my ability to walk,” and got in the habit of taking a walk in the neighborhood around 9:00

p.m.. I didn’t want her to get lost, so I followed her. She took a walk at night two or three times a week.

One day she came back home bleeding from her hand. She seemed to have grabbed the barbed wire in

front of our house. These wanderings were a heavy burden on us, but fortunately it stopped immediately

after she took a pill prescribed by a psychiatrist.

After I came to care for my mother, I couldn’t even go out. However, I always thought I wanted to

shoot my mother’s photo. I couldn’t decide on my shooting procedure, for example, what kind of camera

I would use, and with what composition I would shoot. I bought a medium format camera, a Mamiya

7, but it was not suited for a portraits because it lacked zoom. I decided to use a Fuji GA645Zi, which

I always used for street snaps, and it ended up really working. I could take a bust shot with minimum

shooting distance and easily release the shutter with auto focus.

I started to shoot from September 4th, 2001. I always did it in the morning, because my mother

had a clear memory and she followed my advice in the morning. She often fell into delirium at night and

she was restless or fell asleep. When I woke her up at 6 o’clock in the morning, I got her changed, gave her

breakfast and medicine. The medicine was composed of 6 pills. When the pill got stuck between her

false teeth and her gums, she spat it out. I had to check if she swallowed it completely. Especially, if she

didn’t take her medication for hypertension, her blood pressure would rise rapidly. Special caution was

needed. After I gave her medicine, I took a rest and got around to shooting. I got accustomed to the

procedure, so it took only 10 minutes. My mother didn’t refuse it and she kept quiet and got photographed.

In doing this, I always asked her these questions.

“What is your name?”

“When is your birthday?”

“What was the name of your husband?”

“What happened to your husband ?

“Where did he work?”

I tried to keep these memories in her by asking these questions everyday.

Why did I start to shoot from September 4th? Because it was the day that fate fell on us.

September 4th, 1990, 9:25 a.m. While I was working, my mother called me to say that my

father had a stroke in Ueda city. His condition was bad and we had to go to the hospital at once. The

diagnosis was a critical brain infarction and the doctor said that this week would be the most important

for him. Fortunately, he escaped death but he could not even roll onto his back and was confined to bed.

My very petite mother had been caring for my father, who weighed about 70 kg, wholeheartedly for

about 6 years. My mother developed dementia several years after that, but I decided not to move her

to nursing-care facility. That was truly because I had been watching her caring for my father. When he

failed to move from bed to his wheelchair, she gave me a call for help many times. When he went to a

day care facility once a week, I drove him to and from there. When I came to pick him up at half past

four o’clock, my father and my mother would often wait for me at the window. The scene was still burned intomy memory.

Despite these memories of my father, caring for my mother became really stressful.

We all have our limits of tolerance. The limits vary from person to person. For example, some have

a small capacity, like a test tube, others have a large capacity, like a bucket. Some days there is nothing

in the container, but other days it is almost filled to the brim. When the container spills over, people vent

their frustration. I believe my container is larger than an ordinary person, but my frustration sometimes

spilled from the container during the six years of caring for my mother. That was due to the behavior

unique to dementia. I did understand it was due to the illness, but my frustration slowly, or sometimes

suddenly, collected into the container and spilled from it.

I couldn’t stand my mother changing from what she used to be. I think I tried to confirm my own

horizon and keep my mental balance through the expression of shooting every day.

Furthermore, the moment I released the shutter, I always asked myself how long this was going to

last.

However, I clearly understood I was living an irreplaceable moment.

On October 26th 2004, my mother Iku completed her living and passed away at the age of 86.

Separation, then release from life.

Afterword October 26, 2014 Hiroyoshi Yamazaki

Everything is already contained in my memory. However, these

photographs remind me of the days that I struggled in that dark tunnel

for a little light. When I read the diary again, I found myself reaching the

limit of my patience at that time. I feel a pang of regret because I should

have treated her more tenderly. At the same time, however, I believe I

had a lot of good luck during that time. God could have given us a much

worse scenario.

In editing this photo book, I put my mother’s note written in 1999

at the front. My mother in the photographs has been silent, but with this

note I felt as if she started to speak loudly.

While I was making this book 10 years after shooting these photos,

I had a slight hesitation about publicizing it. However, I desperately

wish that these photographs reach those who are suffering and become

some kind of hints in their lives.

Published in 2015

by Ohsumi Shoten, Publishers

Rm#505, 5th Floor Komazawa Building

5-16-12 Honkatata, Otsu, Shiga 520-0242 Japan

E-mail: info@ohsumishoten.com

Web: http://ohsumishoten.com/

Copyright c 2015 by Hiroyoshi Yamazaki

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior permission of Ohsumi Shoten, Publishers.

Design: Takashi Kitao (HON DESIGN)

Printing: SunM Color Co., Ltd.

English translation: Kazuma Kiyota

English proofreading: Seanacey Pierce

ISBN(japan) 978-4-905328-09-4 C0072

Printed in Japan

Critic ( japanese )

Keijiro hosaka Asahi Shimbun 2015/4/19

Koutaro iizawa Artscape 2015/4/15

Koutaro iizawa Artscape 2015/5/15